by Guest Contributor Alexander Lumans

“Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.”

Ben Lerner. By John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

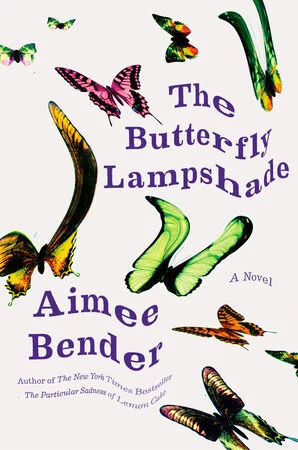

This is the ending line to the epigraph of Ben Lerner’s second novel 10:04, which is taken from Georgio Agamben’s The Coming Community, translated from the Italian by Michael Hardt. It describes a story told by the Hassidim about the future of the world. Permutations of this line appear no less than five other times in 10:04. Among the many roles the line plays in Lerner’s novel, perhaps the strongest is its use as a description of time. Not simply our experience of time, but also our experience of transcending time—our ability to travel through time at different speeds, with our memories and consciousness and imagination as mile-markers. In other words, thought as time-travel. We can revisit our high school prom in the span of two seconds and we can imagine for days taking part in an upcoming car race that will in fact only take two hours; moreover, we can reverse this, too, dwelling on that prom for a week and summing up the race in a montage of minutes. This is the power of writing (and, for the purposes of this essay, prose in particular) because, as Lerner says, reading and writing are “time-based arts.” And this is why time-travel continues to fascinate readers and writers alike, particularly in the speculative genre, where the vivid and continuous dream allows for the suspension of disbelief so that time-travel can occur. We want to time-travel. And reading allows that to happen. This is worth examining from unexpected vectors to better understand time’s role in fiction (however speculative it may be) and how we can better employ it. This is not a novel idea or suggestion, I admit. By the end of this essay, everything will be as it is now, just a little different.

In Denver I live one block from an ornately architectured high school, complete with Grecian gate, mottled red brick under light terra cotta trim, and a clock tower. One night last year, I happened upon an uncanny scene there. I was riding my bike home when I neared the school and saw a strange light streaming down from the five-stories-tall clock tower. That night, as part of the school’s prom, they had hired a Back to the Future re-enactment. This included an actual Delorean parked in front of the school alongside a continuously running fog machine and a long cord of stereoscopic lights stretching from the Delorean’s back hatch all the way up to the clock tower’s face. You could sit in the Delorean and have your picture taken. I still don’t fully understand why all of it was there. But I love it. In 2015, I, a thirty-year-old, in front of a school full of prom-dressed seventeen-year-olds secretly worrying about the future, could sit in a car from the year I was born, reconstructing a scene from a 1985 movie about a seventeen-year-old who travels back in time to 1955 and who spends the plot trying to return to 1985 without having disrupted time’s arrow to the point that he no longer exists in 2015, the future he visits in the movie’s sequel. This is the magic of experience diversifying over seemingly unrelated narratives. And it is that quintessential convergence of time and story: an insignificant moment is made significant through mental time-travel, where everything will be as it is now, just a little different.

Back to the Future re-enactment. Photo by A. Lumans.

Sitting in the Delorean made me think of Lerner’s novel because Back to the Future appears several times in the book—it is, in fact, titled 10:04 because that is the exact time in Back to the Future when lightning strikes the clock tower and sends Marty back to 1985. Lerner’s narrator watches the film twice in the book, both on the nights when a once-in-a-generation storm threatens to submerge New York City. Similarly, at one point the narrator goes to see Christian Marclay’s video-art piece The Clock, which is a twenty-four-hour video of clips from film and television that, in real-time, either show a clock telling the time or show a character saying the time. Marclay’s piece includes the lightning-and-clock tower clip from Back to the Future for part of the 10:04 PM minute. Lerner’s narrator says that while watching The Clock he actually loses sense of time passing. When he wants to know how long he’s been watching, he looks at his own watch, only realizing after the fact that he’s constantly being told what time it is by Marclay’s video and should have no need to wonder how long he’s been there. This is time-travel! Sure, it’s no 1.21-gigawatt-fueled flying car, but it does enact the principle of time dilation. For these reasons and others, 10:04, I believe, is a speculative novel in the guise of a literary masterwork.

Recently, I was in a workshop led by Ben Lerner as part of Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop’s 2016 Lit Fest. Over the course of the week, Lerner kept addressing the experience of time within reading and writing. In the workshopped pieces, whether it was a character shopping in a duty-free store or a character recovering from a car accident, Lerner would point out the experience of the duration of time within a scene and how, often, the experience of that duration felt incongruous with the depicted experience. In other words, the narrative unfolding failed in its specific attempt at verisimilitude. He continually encouraged us to have the reader undergo some version of the duration; in Lerner’s eyes, if something happens too fast, it’s not real. You have to have technologies in the writing to allow time to pass because that’s part of the aesthetic experience of reading. That is not to say you should have moments of complete boring voidness in your text; instead, the best writers are the ones who can make even the most minor of moments expand outward. Nothing necessarily changes physically in that single of second of looking at a watch, but the narrative creates the sensation of change: “Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.” To ignore this technology of employing duration is to deny the work’s potential, if not its very humanity. As 10:04’s narrator says, “Because the world is always ending for each of us and if one begins to withdraw from the possibilities of experience, then no one would take any of the risks involved with love.”

My parents are calling this year “the year of afflictions”—and it’s only halfway over. We have friends and family undergoing divorces, major surgeries, chemotherapy, thoughts of suicide, attempts at suicide, death itself. These afflictions seem more rampant and clustered than any year prior. Which may very well be true. Past years’ afflictions feel more spread out. As if the decrepit road behind us extends deep into the rearview mirror, but the immediate road ahead is so full of potholes that you cannot drive a foot without getting a flat. But this is our narrative experience of these events. This is us time-traveling. Will my parents experience future years with more afflictions? Likely. Will my family experience future years with fewer afflictions yet more deeply heartbreaking ones? Also likely. I want to tell my parents: “Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.” But what will win out in the narrative of memory? Which time will seem—feel—longer or shorter, or, for that matter, simply different? These questions are the heartbeats of fiction writing.

As HP Lovecraft writes in his essay “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction”:

“The reason why time plays a great part in so many of my tales is that this element looms up in my mind as the most profoundly dramatic and grimly terrible thing in the universe. Conflict with time seems to me the most potent and fruitful theme in all human expression.”

I agree with Lovecraft on this. Time is the only thing we cannot, without question, change. Which is what characters struggle with most: that which is unalterable. And this is, ultimately, why we write speculative fiction: to alter time. Whether it’s to predict a dystopian scenario in a far-more-than-likely future like Claire Vaye Watkins’s Gold Fame Citrus or whether it’s to go back in time to alter the often horrific events of the past like in Stephen King’s 11/22/63: the afflictions spread forward and backward for us, as if time itself were a physical condition, causing us symptoms of regret as well as hope.

While visiting my parents recently, I broke out my old Sega Genesis for the first time in a decade. In addition to trying to figure out how to hook up a 1989 gaming console to a 2015 flat screen TV, I also had several strange moments of palimpsest time. I decided to play one of my favorite games: Rock N’ Roll Racing. From 1993, it’s a game in which you have traveled to the future to race against aliens on other worlds while listening to MIDI versions of earthly rock songs ranging from 1982 to 1959. I realized quickly that it was the same game from my memories, but I was somehow much worse at it. It had the same graphics, but they were more pixelated than I remembered. I was thinking the same thing as 10:04’s narrator: “nothing in the world, I thought to myself, is as old as what was futuristic in the past.” My mother even walked in and said, “This looks just like a picture of when you were fifteen—except for the beer bottle now,” when she might as well have been saying, “Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.”

My mother was watching me time-travel. If this were a scene in a novel like 10:04, you can bet there would be moments in which the narrator would recall other hopes of childhood and other regrets of adulthood. The Sega Genesis (and the etymology of “genesis” is not lost on me here) would be the metaphorical Delorean and Rock N’ Roll Racing the lightning strike. Moreover, the scene would be doing other time-travel work; the Oxford Reference of Roland Barthes’s “reality effect” from his 1968 essay “The Reality Effect” says:

“The small details of person, place, and action that while contributing little or nothing to the narrative, give the story its atmosphere, making it feel real. It does not add to the plot to know that the character James Bond wears Egyptian cotton shirts, but it clearly does add considerably to our understanding of him. By the same token, knowing that he buys his food from Fortnum and Mason makes him more real.”

By dilating our attention onto a seemingly insignificant detail (a dusty Sega Genesis) an author can world-build in her fiction, which is vastly important not only to the world but also to a reader’s experience of the characters’ experience. And those off-duty details are just as necessary as on-duty details. Through that dilation on an unimportant object, an author may create the experience of duration, and therefore enact time-travel. The Sega Genesis won’t come to play a significant role in the intergalactic treaty being negotiated on Discworld—it’ll simply stay a Sega Genesis—but it does give the opportunity for a powerful treatment of slow-time in which the Genesis opens up new temporal doors for the reader.

I realize I have likely conflated reading and writing in this essay, but that in and of itself is interesting: what I write now becomes the now of a future reader, but it also becomes my past as well as the reader’s past, with recurring appearances in both our futures. This temporal layering is a central focus for the narrator of 10:04. The novel raises the question of what is real experience: the first event or the recalled event or the revisited event or all of the events together or none of the events at all? And whose experience is it? Is a suicide the sole experience of the dead, or is it the possession of everyone else left behind? It’s a question of time.

In 10:04, when the narrator is watching Back to the Future, he watches it projected onto an apartment wall. And silhouetted on that same wall are the branches of a tree outside the window. The branches extend simultaneously into the past, the present, and the future. For those branches, everything will be as it is now, just a little different: “The shadows of the trees bending in the increasing wind outside her window moved over the projected image on the white wall, became part of the movie, as if keeping time with the zither music; how easily worlds are crossed, I said to myself.”

This is the difference between “reading time” and “text time.” How long it takes you read about a character’s bike ride is very different than how long the bike ride takes. It’s important, though, that the reader undergo duration in the reading. One day can last for an entire novel, or one novel can cover thousands of years. Either way, there should be an attempt by the writer to guide you, via fictive time-travel, toward a suffering of the tangible. (I use “suffering” in particular because its original Latin meaning “to bear, undergo, endure, carry or put under” is more apt to Lovecraft’s conflict, Lerner’s narrator, Barthes’s reality, and my speculative notions. Bearing time, undergoing time, enduring time and carrying time are all very different ways to engage with it, which is the kind of time-traveling I’m discussing.) I’m not saying a writer’s treatment of an event and the reader’s reading of it have to adhere to a second-for-second ratio—that might very well be impossible except in the case of Marclay’s The Clock. But the more you visit a moment in time, the more it becomes a moment out of the ordinary, and the more it takes on time-traveling proportions. By simply rereading the line “Everything will be as it is now, just a little different,” your meaning-making acquires new wrinkles. And by revisiting a moment—by time-traveling through the medium of fiction—you are making the world to come and you are making it a little different than what it once was.

Guest contributor Alexander Lumans was the Spring 2014 Philip Roth Resident at Bucknell University. He has been awarded fellowships to the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, The Arctic Circle Residency, VCCA, Blue Mountain Center, ART342, Norton Island, RopeWalk Writers Retreat, Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, and Sewanee Writers' Conference. He received the 2016 Wabash Fiction Prize from the Sycamore Review, the 2013 Gulf Coast Fiction Prize and the 2011 Barry Hannah Fiction Prize from The Yalobusha Review. His fiction has appeared in TriQuarterly, F(r)iction, Bat City Review, Cincinnati Review, and The Normal School, among many others. He has also published poetry, nonfiction, and essays, in Guernica, Glimmertrain, The Los Angeles Review of Books, American Short Fiction, among others. He graduated from the M.F.A. Fiction Program at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.