Yesterday evening, Kazuo Ishiguro accepted his Nobel Prize for Literature and delivered a thoughtful, at times stirring speech on his lifelong preoccupation with memory and forgetting, the progress of nations, and human relationship. These preoccupations lie at the heart of his 2015 fantasy novel, The Buried Giant: "Does a nation remember and forget in much the same way as an individual does? What exactly are the memories of a nation? How are they shaped and controlled? Are there times when forgetting is the only way to stop a society disintegrating into chaos or war? On the other hand, can stable, free nations really be built on foundations of wilful amnesia and frustrated justice?" These questions have come back with frightening force as Ishiguro's Britain and our America face the revitalized forces of racism, inequality, and mutual suspicion, "stirring beneath our civilised streets like a buried monster awakening."

The Buried Giant imagines an ancient Britain plagued by a magical mist of forgetting, exhaled by the dragon Querig. We follow Axl and Beatrice, an elderly Briton couple, as they follow a knight, Wistan, on his quest to slay Querig and free the land of its curse. But is the curse, in fact, the only thing keeping the land together? Will Wistan plunge a fragile Britain into a renewed cycle of reprisals between Britons and Saxons? And hey, what's up with that boatman at the end—is he, like, Death? At the time of its release, The Buried Giant was heavily criticized for its rather off, even bizarre evocation of the fantasy genre. But some stories have to be told outside the forms that trap us inside stale thinking. Otherwise, we get those darker fantasies and clichés currently running around D.C. and Downing Street.

In his Nobel lecture, Ishiguro closed with a plea to diversify literature, certainly in terms of welcoming voices from underrepresented literary communities, but also in terms of genre: "The next generation will come with all sorts of new, sometimes bewildering ways to tell important and wonderful stories. We must keep our minds open to them, especially regarding genre and form, so that we can nurture and celebrate the best of them. In a time of dangerously increasing division, we must listen. Good writing and good reading will break down barriers. We may even find a new idea, a great humane vision, around which to rally."

We couldn't have put it better ourselves. I mean, obviously. It's Ishiguro, after all. In honor of his well deserved Nobel prize, below is our April 3, 2015 anthology of mini-essays on The Buried Giant. Congratulations, Ish! And thanks for the memories.

– Theodore McCombs, Ishiguro fanboy, for Fiction Unbound

"Shall we take a funny one?"

Last week, we posted our pile-on review of Kazuo Ishiguro's seventh novel, The Buried Giant, released earlier this month. That weekend, we gathered at the University of Colorado, Denver to hear Ishiguro himself discuss the novel, and on Saturday, he delivered a shop talk at the Lighthouse Writer's Workshop. Our own Theodore McCombs even cornered him for a selfie, and had the pleasure of explaining why one of his fans asked him to sign a book, "You do you," and what on earth that meant.

Today, we return to The Buried Giant and its mists. We come not to critique the Giant but to bury him, in analysis. Here, then, are five speculations on the novel, the dragon, the dungeons, mists, myths, memory, boatmen and women, allegory, ogrelory and, yes, fantasy.

Amanda Baldeneaux, on Avenue 'Q'

The Buried Giant is the story of a quest. The primary travelers, two elderly Britons in post-Iron Age England, move none too quickly on their quest to find their almost-forgotten son. Their excursion takes an unexpected turn, though, when the two find themselves in a quagmire of quixotic errands to quiet the dragon Querig. Querig, a wily, secretive beast, sleeps in a hidden lair somewhere in the countryside, exhaling an amnesiatic fog over the land.

Katherine Pyle, Dragon rearing up to reach medieval knight on ledge (1932).

The trouble with living in a fog of amnesia is the number of questions that arise regarding one's past; but the benefit is the forgetting of quarrels. When quarrels lead to slaughter, perhaps a little forgetfulness isn’t so bad? The forgetful can’t know this, though, and so the rag-tag quintet, comprised of the elderly Beatrice and Axl, Sir Gawain, Wistan the Saxon warrior, and little Edwin, quest on to quell the dragon’s forgetful reign.

By now, you may have guessed our letter of the day: 'Q.' The letter 'Q' and its love affair with the letter 'U' lends itself to the very heart of the word 'question.' In Latin, one would ask 'quod' or 'qualis' for “what?”, and in Spanish 'que,' in French 'quel,' and so on. The letter 'Q' has more than a few origins stories, one of which is that 'Q' stems from the Egyptian hieroglyph for a cord of wool. It seems fitting, then, that Ishiguro named his brain-fog breathing dragon Querig, as she has a knack for making the townsfolk a bit woolly in thought.

In Doctor Who, one of the Doctor’s many alien foes tells him repeatedly: “Silence will fall when the question is asked.” In The Buried Giant, the same ominous prophecy rings true: when the people begin to ask questions and learn who they really are, what they’ve done, and what’s been done to them, the silence that falls will be the silence of isolation, of festered wounds, and of a battlefield after the war. Ishiguro forces his readers to ask their own hard questions: would we better off in a forgetful peace, or in a world of remembered slights, and quests for revenge?

Since we live in a world without a Querig, though, Ishiguro demands we question ourselves: Where in the human heart is forgiveness found, and are we strong enough, as a society, to cultivate it, so that we may quash our perceived slights and live in a true and lasting peace? One can only hope that Ishiguro’s dream of prolonged peace is a vision that is acquirable, and not as quixotic as the old warriors of his tale. It’s up to us the reader to pick up the task of breaking the cycle of violence, and to not quail in the face of letting go, and query when it is quite okay to forget.

Lisa Mahoney, on Death by Water

Gustave Doré, Phlegyas ferries Dante across the Styx (1861)

Ishiguro’s aging protagonist couple are mysteriously drawn to a river, and most of us are familiar with the Western-canon stories in which crossing a river indicates dying. As we know, Charon ferries the dead across the rivers Styx and Acheron in Greek myth, as Phlegyas does in Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Only heroes or people with god-level skills, like Hercules and Orpheus, can cross the Styx alive and return alive. But the belief that the dead exist in a land under, on, beyond, or in water is more universal than I’d realized.

In some Celtic stories, the dead resided on an island in the west, a close parallel to The Buried Giant. The Norse, too, believed a river separated the living from the dead, the river Gjoll, and the bridge across it shook if a person tried to cross too soon. Further east, Indian stories hold that the Vaitarna River lies between the Earth and Naraka, the god Yama’s realm of the dead. The good bypass the river, but sinners can get stuck in a bloody, impassable morass. Even further east, in Japan, good souls cross the Sanzu River using a bridge, the not-so-bad ones can ford it at a rapid, but dead sinners are plagued by the river’s dragons and demons.

Gursahai, The Court of Yama, God of Death (c. 1800).

These river myths could have common roots in the far-flung Indo-European tradition, but this would not explain the similar yet lovely stories from southern continents. Peruvians tell us that the Vilcanota River is a reflection of the Milky Way whose water circulates between heaven and earth. And finally, the Ashanti tradition of West Africa holds that souls can be reunited in the afterlife with those who have crossed the river before. In one story, dead Ashanti widows advised a heartbroken widower to remarry and be happy.

Let’s hope that Ishiguro was modeling these netherworlds, not the more stygian Greek variety.

Theodore McCombs, on the Giant's Castle

Last week, CS Peterson and I discussed Ishiguro’s ambiguous use of allegory—how the lack of a clear referent creates tension between text and reader, prompting an emotion of distrust or, at least, a feeling of missing something important.

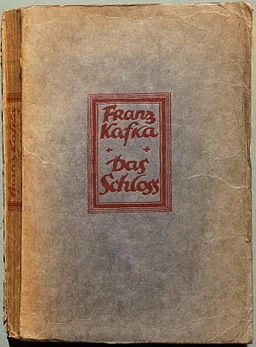

Kafka's The Castle (1926).

Kafka uses this stray pointer technique to great effect in The Castle, creating a world in which the land surveyor K. desperately tries to get into, well, a castle—which, as far as we can tell, is a bureaucratic center of powerful, inscrutable officials. Is it... Heaven? The modern technocratic state gone crazy? What does it all mean? Scholars are still arguing about it. I side with those who think The Castle is, at least in part, about this very pressure of inscrutable meaning, the conviction it all must mean something, and how one can possibly proceed when that conviction is frustrated. The Castle is a castle.

Jan Provoost, "Christian Allegory" (c. 1510-1515).

Speculative fiction has a long tradition of explicit allegory, dating back to Pilgrim’s Progress and further. C.S. Lewis clearly intends The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe as a retelling of Jesus’s crucifixion (happy Good Friday!), as Robert Heinlein clearly intends Michael in Stranger in a Strange Land as a Jesus figure. But Ishiguro’s boatman, especially in his first appearance, feels very much a figure out of Kafka’s playbook. Our first sight of him, a weary, tonsured man waiting out the rain in a ruined Roman villa, while some crone torments him by stroking a knife along a trembling rabbit, is so bizarre it provokes that intense pressure of meaning. It is, in fact, like one of those early Christian allegorical paintings, unintelligible except by reference to symbols and interpretation. The way the boatman lets slip inside information to Axl and Beatrice, because they’ve caught him in a funny mood, reminds one too of the castle official Brügel, whom K. surprises in his bedroom in the inn, and in his dreamy torpor seems ready to grant K.’s impossible desires.

By the end, of course, the boatman very much is Death—the allegory becomes all but explicit. The crystallization of this allegory thus parallels the process of the characters’ obscured memories gradually clarifying, out of the thinning mist.

What I'm saying is, clearly the boatman is Jesus.

CS Peterson, on the Triptych of the Sexes

My early experience reading Ishiguro lead me to believe he is nothing if not careful. After listening to him talk about the craft of writing, and his process in particular, last weekend, I fully stand by this belief. Therefore, I went back to look again at the placement of male and female characters in The Buried Giant, trusting that each character has been put there with thoughtful intention.

It is a quiet book, even in its most dramatic moments, a meditation on relationships and memory. I began to imagine the characters in the book represented in a triptych, with each wing its own set of panels, arranged to support contemplation:

In the central panel, Beatrice leads Axl, with their son painted in colors which render him almost invisible. On the left wing, three panels depict the other women in the novel, and on the right, Axl is echoed in a trio of men.

Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece (1430-1432). An excellent example of a complex polyptych, a triptych of many-paneled wings.

The three most prominent women to figure in the supporting action we see through the eyes of the Saxon boy Edwin. First is a maiden, bound by three male companions and abandoned in the rushes by the river. She initially refuses Edwin’s offer of help, but then accepts it and weeps. The second is Edwin’s mother, who has also been taken by traveling men. The dragon takes up her voice, calling to Edwin to free her. The dragon Querig is the third, an aging beast, who was taken and bound by a group of Arthur’s knights. The men co-opted her magic breath to enforce a strange peace on the land. A chorus of crones complete the depiction of women in The Buried Giant: the widow harassing the boatman, and her sisters hurling abuse at Gawain, all for depriving them of the memories of their husbands, separating them from even the memory of love.

On the other wing are three men, all cast in their relationship to courage in battle. Edwin is the youth, almost a man, ashamed at running from a fight. Wistan is the warrior in full flower of strength, on a mission of vengeance for the wrongs against the Saxons, but with conflicted feelings towards to the kindly old Briton couple. Britons raised Wistan; many were individually kind to him. Yet the Britons and Saxons slaughtered each other. It is his duty to remember that, right? The third on the men’s side is Sir Gawain. He appears to act the sage, yet is full of half-truths, defending his actions with the question, “if you were there, would you not have done the same?”

The placement of supporting male and female characters in the book echo and expand the relationship between Beatrice and Axl through every age of man and in ever widening circles.

Mark Springer, on Ishiguro the Dungeon Master

There is a secret hidden in the mists of The Buried Giant. I don’t mean the secret of the forgotten past or important stuff like that. I mean the untold (and completely untrue) story of how Ishiguro wrote the first draft of the novel as a Dungeons & Dragons fantasy role-playing adventure.

Is The Buried Giant fantasy or not-fantasy? It's all in the eye of the beholder.

Imagine a late night of caffeine-fueled creativity. Dog-eared pages of an old Monstrous Compendium are scattered about Ishiguro’s office as he pores over D&D rule books. His elderly protagonists, Axl and Beatrice, are traveling on foot through a dangerous landscape. The storyline feels a little flat at this point because Axl and Beatrice are unsure of their purpose, so Ishiguro does what all Dungeon Masters do when an adventure bogs down—he rolls for a random encounter. “Fates, do thy worst!” he cries, perhaps too enthusiastically, as the dice clatter across his desk. One bounces off a half-empty Mountain Dew can. The other momentarily disappears beneath a family-size bag of Doritos but is easily recovered. Ishiguro checks the result against his random encounter table for temperate mountains, post-Arthurian mythical England: dragon. Bilbo Baggins and Beowulf leap to mind. “Yes!” he shouts. “Shit just got real.” He is about to fulfill every Dungeon Master’s dream—an epic battle with a legendary creature of awesome power.

But now Ishiguro has a different problem: Axl and Beatrice don’t stand a chance in this fight. They’re just an elderly couple out for a stroll, no weapons, no spell-casting abilities. One combat round and they’ll be a snack for the dragon on its way to ransack Esgaroth and the Lonely Mountain.

Not to worry, thinks Ishiguro. Every adventuring party needs a warrior to swing a sword and jangle about in chain mail. So he pencils in a Saxon warrior and a noble knight, Sir Gawain, then adds Merlin the sorcerer for good measure. Ishiguro chuckles. "You shall not pass!" he whispers as he picks up the dice to roll the next random encounter. Ogres? Quite right...

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.