China Miéville has won the prestigious Arthur C. Clarke Award three times, the British Fantasy Award twice, and a Hugo award. Theodore McCombs and Lisa Mahoney appreciate two of his books, one older and one just released.

Theodore McCombs, on The City & the City (2009)

What does it mean to be in Besźel? What does it mean to be in Ul Qoma? The reader of Miéville’s The City & the City will struggle the length of the novel to figure this out, piecing together semi-obscure cues from the characters’ words and actions. This must be what it is to grow up in Besźel and Ul Qoma: trying to navigate rigidly policed boundaries that no one will really explain; taking loaded hints from clothing, posture, and color; ‘unseeing’ the other that walks beside you. And isn’t this what it is to grow up in any socially policed binary, be it ‘male’ and ‘female,’ or ‘white’ and ‘non-white’?

Besźel/Ul Qoma is a split city, like Berlin or Budapest, but instead of a wall or river, what divides the two halves is purely psychosocial. Certain streets and buildings are deemed in Besźel, others are in Ul Qoma, and the rest are ‘cross-hatched,’ i.e., in both cities. Residents of one city must not cross boundaries or even see things—people, buildings, speeding cars—that are in the other city. Literal, topologic neighbors in different cities can visit only after going through a central checkpoint and calls are international. If you break these rules, you’ll be disappeared by a shadowy, highly local enforcement group: Breach.

The City & the City follows a Besźel homicide detective, Inspector Borlú, as he investigates a Jane Doe dumped in the Besźel slums, but murdered in Ul Qoma. If this immediately intrigues you, you will love this novel. It’s a drama of rules and jurisdictions, walking logic puzzles, ingeniously threaded needles—lawyers and philosophers will goggle at the fun Miéville creates from his inventive premise. The rest of us, well, we’ll have to make do with the plot and characters. These are good in their own right, but probably not enough if the premise just annoys you. Myself, I found Borlú’s strange and existential journey deeply moving, not to mention wonderfully crafted: I kept pausing at page 100, 150, 200, etc., to look backward and marvel how far this short, tightly plotted book had carried me. This is the rare novel with a truly original speculative premise that is both too clever by half and profoundly realized, forcing us to examine what imagined boundaries we unwittingly enforce.

Lisa Mahoney, on This Census-Taker (2016)

Why did I enjoy Kracken and The City and the City, and look forward to Miéville's latest, This Census-Taker? Because Miéville's works demand active, involved reading. Don’t spoon-feed me detailed histories and explanations of the rules of the speculative realm I’m going to enter, just sketch it out and throw me in there (setting has a supporting role, after all), launch a gripping tale with mystery and danger, and hook me for the journey.

In This Census-Taker, Miéville does not disappoint.

Unlike in Miéville's longer works, in This Census-Taker, the imagined world’s broken political systems and the magic that may or may not saturate the boy’s rickety home aren't gradually clarified to us because they are not central to the nine-year-old narrator's circumscribed world. The boy lives on a mountain slope enough like our world that we recognize it, but the low level of technology, plastic trash, broken bridge and gangs of orphans hint at some apocalypse in the recent past. The boy’s father is a refugee from another country, having fled from something unspecified. He makes keys that seem to solve people’s difficulties, but because the boy has grown up in this world, he is not as curious as an adult stranger would be. We, following through the eyes of the boy, never need the exact magical or political systems explained to us. They are not what is important. What is important is that this is a story about a boy whose father has a violent temper and about the shift in the boy’s relationship with him as his fear of the man increases.

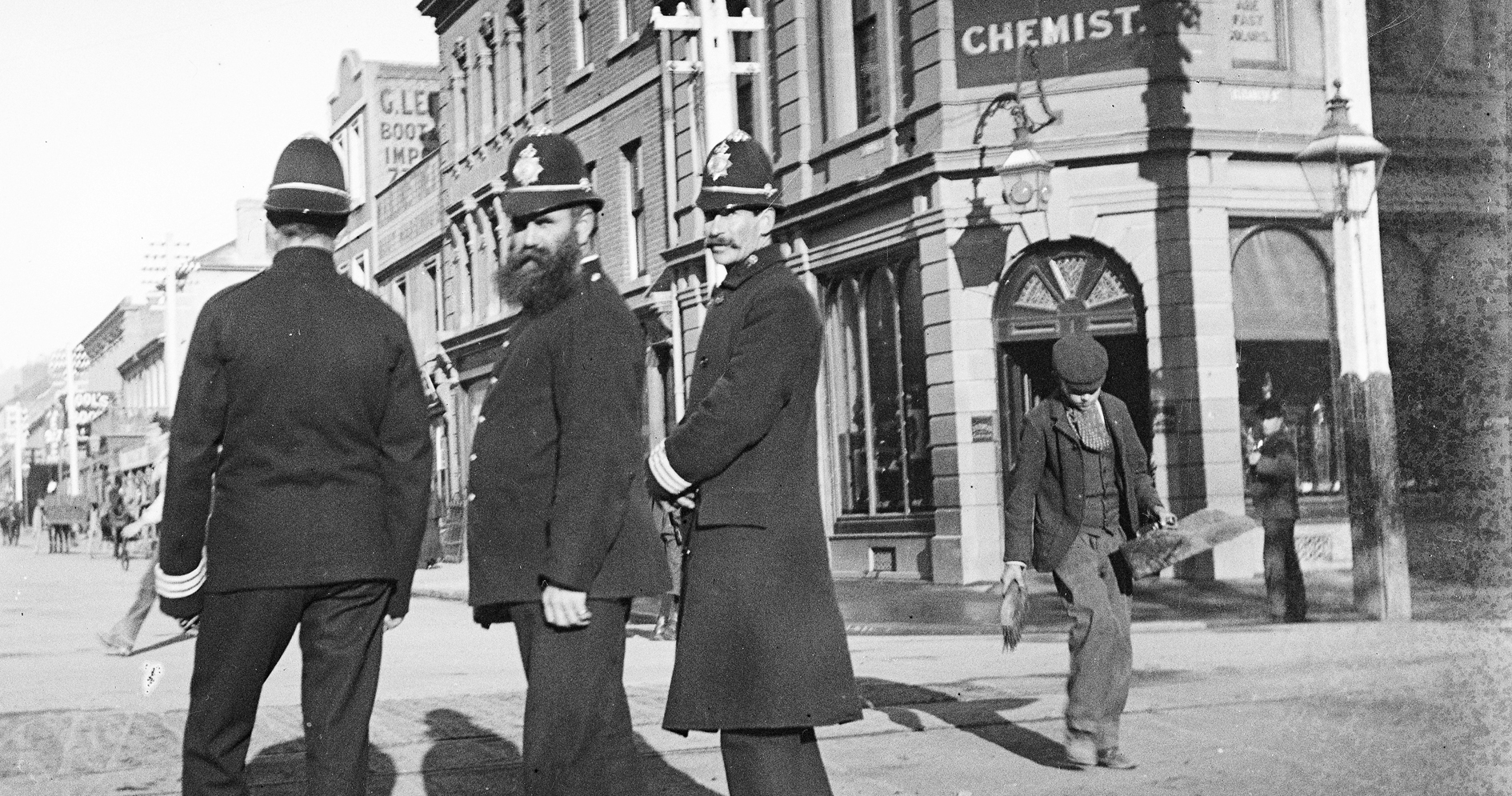

Police in Hobart and a boy minding his own business, c1900, from Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office Commons.

The novel opens in Miéville style, with an action-packed mystery: the boy runs down into town, and, befuddled, reports that his father has killed his mother. The rest is a universal story about the child’s survival, and how he makes friends with orphans who inspire hope in him that he can change his life.

But the law, a ragged holdover from more organized times, disagrees. Miéville, who studied international relations, often touches thematically upon social and class inequities, and, as Ted mentioned above, the ruthlessness of authority figures.

I think that in This Census-Taker we see some of Miéville's ideas play out in miniature: a boy is sent back to a father, despite that the townspeople suspect he is abusive, because the law says that a boy belongs to his father. At the end of the first chapter, we are warned that the law won’t be on the boy’s side, even though he’s coming to report a murder in his own family:

“It was the law of this town to which we were subject. When I came down that day, I wasn’t running for the law, but the law found me.”

And, in another instance of injustice, the law takes the boy from the protection of the gang of orphans which had adopted him:

“There were three other full-time and uniformed officers using the schoolroom as their temporary headquarters. They muttered to each other, they seemed edgy. They all but ignored me, except for the big policemen: he beat me. His attack was offhand and calm. He explained with passionless ill-temper that this was what I got for disobeying the law that made clear I was my father’s.”

Interestingly, in this novel-within-a-novel, full of gorgeous prose, and vague and disturbing imagery, the ultimate solution is extra-legal, though by a force that claims jurisdiction in the case all too adamantly.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.