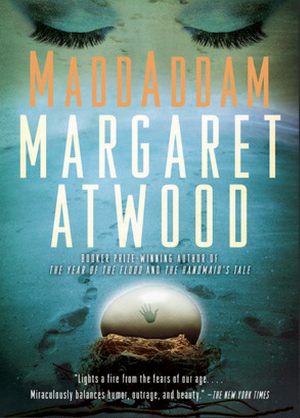

In anticipation of Margaret Atwood’s new novel, The Heart Goes Last, which published on September 29, Fiction Unbound is looking back with awe-filled wonder on the author’s post-apocalyptic MaddAddam trilogy: Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009), and MaddAddam (2013). Today, Unbound Writer CS Peterson shares her appreciation of MaddAddam.

Spoilers, lots of them. Existential triggers. You have been warned.

MaddAddam is the story of the survivors. Specifically it is the story of how the horrors of the past become codified into a child-appropriate cycle of bedtime stories told by the rifle-toting Toby to the big-eyed polyamorous Crakers, in whom there is no guile, not a glimmer. It begins at the moment Oryx and Crake ends. Toby and Ren have just rescued Amanda from two vile painballers when Snowman-the-Jimmy stumbles into the ring of light around their campfire. The Crakers, genetically engineered by Crake to be in a perpetual state of innocence, show up and naively untie the captured painballers. So Toby and the girls bring Snowman and the Crakers back home for safekeeping.

Home is a small survivors compound made from the old cob house, a former garden stand, now fortified with a fence, vegetable garden and, eventually, beehives. Toby lives with Zeb, who also survived, along with a clutch of MaddAddamites. (You may recall Zeb as Toby’s rough-around-the-edges love from her time as Eve Six at Edencliff with the God's Gardeners in The Year of the Flood.)

Exposition is the speculative writer’s bane. Atwood manages to turn that bane into a blessing for this tour de force finale to her apocalyptic trilogy. She has built three audiences into the narrative. First are the Crakers, who demand a story from Toby each night, since Snowman-the-Jimmy is ill. The second is Toby, who asks her lover, Zeb, for the story of his life, so she will have something to tell the Crakers. Zeb’s pillow talk is a rich and roiling poetry of obscenity. Give yourself a treat and read it aloud. Watching Toby translate Zeb's luscious, decadent snark into the children's bible version that forms the nascent Craker mythos is the fun part of Atwood’s novel.

The third audience is you, dear reader. Moments of direct address increase as Atwood places the reader first in the audience with the Crakers and then in bed with Zeb, listening to stories. Toby has a reading, writing, storytelling apprentice in Bluebeard, a Craker child who attaches himself to Toby and grows to manhood over the course of the novel. In the end he addresses the reader directly, as a voice of one dead in the past, to the ears of one cast into the unknown future and looking back.

“There’s the story, then there’s the real story, then there’s the story of how the story came to be told. Then there’s what you leave out of the story. Which is part of the story too.”

Atwood has used this device before, in “Time Capsule Found on the Dead Planet,” for example. As a reader it gives me a nauseating experience of time travel that I find deeply disturbing. This device of Atwoods disables my ability to separate my present passive acquiescences and active choices from being complicit in making her darkly imagined worlds a reality. It shatters my passive fantasy that 'it will all come right in the end.' The whole thing gets very meta.

Synchronicities pile on as Atwood’s tale advances. All the characters seem to have bumped into each other, like cue balls on a pool table, as part of the small privileged group that ended up destroying the world. Atwood has some fun, tying together all the loose threads in the past. It's a small world when you rub shoulders with the one-percenters.

Synchronicity is defined, by Carl Jung, as a set of coincidences that have no causal relationship, but are nevertheless meaningful (yes, it’s also a song by the Police that dredges up cringe-worthy high school memories of mullets and baggy pants). Your average person has two synchronistic moments a year. Personally, this week has put me over quota.

While I was in the midst of writing this appreciation, one of my students at school wondered about mass extinctions. So she and I spent the better part of a day journaling our way through the fossil collections at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, paying attention the ebb and flow of life over time.

Extinction events as seen from the ocean, by Robert A. Rohde

Before that day I knew, in a general way, about the big five extinction events. However, on our walk through time we discovered that there haven’t been just five, there have been at least five times that many. Yes, twenty-five times when life on earth came right up to the edge of blinking out. And I mean really close to the edge - two hundred and fifty million years ago, at the boundary of the Permian–Triassic period, 97% of all species in the fossil record went extinct. The chief cause was climate change, triggered by a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere when Siberian volcanoes burnt up vast reserves of coal that had been trapped in the earth's crust eons prior. I gathered my mental and emotional resources, ready to help my thirteen-year-old charge surf the looming wave of existential angst, when she surprised me, as thirteen-year-old charges are wont to do.

“Isn’t it amazing how life can bounce back?” she said. “Maybe mass extinction is necessary for life to evolve. I mean, would we even be here if these extinctions hadn’t happened?”

She is right. And we could go bigger. Consider the sun. I spent time with another student studying the mechanics of stars. Our little star is many generations on from the big bang. Supposing for the moment that life is not unique to the Earth. Might whole planets full of life have been 'cleared away' in making room for ours? It boggles the mind.

The end of all things for the system around that super nova in the bottom left corner. Imaged by NASA/ESA, The Hubble Key Project Team and The High-Z Supernova Search Team

It really does. Incomprehensible horror is disorienting, a dissonant chord we are compelled to correct. And we fix it with myth, with story.

A third student is studying the holocaust, and she has been looking at the writings of survivors. Judith Kalman testified as a witness in the war crimes trial of Oskar Groening this past spring. Her older half-sister, Evike, was murdered in Auschwitz at the age of six, long before Judith was born. How does a child live with this knowledge? With a story.

“As a child I formed a strange myth to explain the baffling circumstances of my existence. There must have been something wrong about the old, beautiful way of life that my father extolled in his stories of the past.... I came up with an answer that makes sense only to a child. For some reason, my sister Elaine and I had to be born. If we were meant to be, then it followed that Evike and her world were not. It was that simple.... From this hypothesis, the solution to the terrors that might befall us followed. Everything bad that could happen to a family had already struck my father and mother. The horrors had come before and thus wouldn’t come again. Elaine and I by extension were inoculated against disaster. The suffering that, as humans, we continue to inflict on one another defies our understanding as adults, let alone that of a child. I offer that in my defense, as well as the ego-centric world view native to childhood.”

"Crake cleared away the chaos to make a place for you," Toby says to the Crakers. We are tiny, daily creatures, though. Humans can’t live on scales large enough to truly comprehend chaos, extinction, and evolution; our concerns are small in comparison, but no less important to us. Toby spends a great deal of time worried about her relationship with Zeb, and jealous of the younger women. Does he love her? Wouldn't it make more evolutionary sense for him to want them? And what right does she have to stand in his way if he should be interested, what with the human species on the brink?

“This is how it starts, among the closed circles of the marooned, the shipwrecked, the besieged: jealousy, dissension, a breach in the groupthink walls. Then the entry of the foe, the murderer, the shadow slipping in through the door we forgot to lock because we were distracted by our darker selves: nursing our minor hatreds, indulging our petty resentments, yelling at one another, tossing the crockery.”

There is so much more to appreciate in this book. Toby's transformation into a priestess by means of bees and the spirit of dead Pilar. Her vision of the pigoon mother and young transformed into something like the ancient sow goddess of the east. The culture of the pigoons, the negotiations between human, pig and Craker. The Craker/Toby co-creation of the godlike Fuck, who flies through the air to aid any who call on him in time of need by intoning "Oh, Fuck!" Jimmie's tears when he finds the bones of Oryx and Crake, Bluebeard's shock as he begins to understand. The death of Jimmy, Toby, Zeb and Adam, the birth of many babies. It is, as one reviewer alluded, like trying to describe the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

The many breasted Diana of the Ephesians - harkening back to the sow goddess of the East, harkening forward to Toby's vision at Pilar's grave. Photo by David Bjorgen

Near the end of the novel, after the battle with the two painballers who have been lurking in the background since page one, the young Craker, Blackbeard must tell the nightly story in place of Toby. He must eat a fish, a ritual established by Snowman-the-Jimmy. But Crakers are hardwired against eating animals, so it pains him to do so. Blackbeard pulls his experience in and endows the ritual with meaning in terms of life and story. "First the bad things," he says, "then the story."

Post Script: Atwood famously grounds her fantasies in reality. The MaddAddam trilogy is a work of fiction; however, Atwood says, "it does not include any technologies or biobeings that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory." If you are interested in seeing these technologies, biobeings and constructions, Atwood keeps an up-to-date flipboard of these here. Someone also put up a version of extinctathon here. Fun for all!

In a world on the brink of collapse, a quest to save the future, one defeat at a time.